Allocators Are Never Fired for Buying Large Funds. True or False?

I was speaking with a Swiss allocator the other day about what he was looking for with regard to fund selection. The allocator had a combined $25 billion AuM and plenty of money to allocate to Absolute Return UCITS. The metrics were quite simple: the fund needed $125 million in the vehicle, a three-year track, and a correlation of 0.4 with the equity markets. If those boxes were ticked, then any fund would be a contender for an allocation.

The problem is that the field is very limited. Most Hedge Funds come close to fulfilling these requirements. However, the structure (UCITS) and the AuM cancelled out a lot of opportunities to invest in good funds.

The allocator was extremely frustrated with their position. Typically, as soon as they are able to allocate to a fund, the allocation can be finished within a week because demand is so heavy.

Of course I found myself sympathetic to the allocator who must have a challenging job trying to find these funds. The market impact of a $15 million allocation is tiny when running $25 billion across portfolios.

When you understand the allocator’s predicament, you understand the gridlock that part of the industry is in. If an allocator invests more than 10% of the fund’s AuM, then they end up owning a large part of the business. If a manager has a $5 million fund and $20 million managed account, then pumping $100 million into another managed account will probably require the manager to invest in infrastructure to reflect those changes. If that account redeems, then the fund manager’s house of cards crumbles. Essentially, the allocator ends up owning the business. For many fund managers, this seems like an acceptable gamble to take since they may be able to leverage one large allocation into further allocations.

However, the allocator isn’t here to own businesses. They want to be able to move in-and-out of funds based on the funds’ merits and market conditions at the time. How can a small fund compete for a ticket with a large allocator next to a large fund? The honest truth is that it probably can’t.

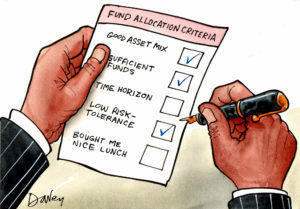

Performance is what fund managers judge themselves by. However, experienced professional allocators are forced to consider a whole number of variables. Oftentimes, we find fund managers oblivious as to why they get passed-by: Wrong or uncompetitive fee structure, liquidity mis-match, better competitors, etc.

So what is the solution?

Well, hard work and sound business development practices. Ticket sizes grow as fund AuM grows. Asset raising momentum is important. If a fund isn’t actively raising money, that is a warning sign for the allocator. Large allocators don’t necessarily want big names, but must allocate to them because of the amount of money they are managing. We know this because we have seen many allocator portfolios. Most will often admit that it is hard to differentiate between other large allocator portfolios because there are only so many large funds available.

Reputational risk is something that allocators are very cognisant of – it doesn’t reflect very well on an allocator if a fund they have supposedly undertaken extensive due diligence on goes into administration. A recent case where this nightmare became a reality was the collapse of the British tycoon, Neil Woodford. The positive externality resulting from this scenario, from an allocator’s perspective, is the increased liquidity transparency for portfolios, allowing allocators to gain a better understanding of what they’re investing in.

There is an opportunity for the smaller and more ‘agile’ managers. When some funds get to a certain size, it can limit their own investment universe. This is most notable for funds that are allocating to smaller companies on the market cap scale, where their allocations are likely to be fairly sizable relative to the company. Their investment could end up having meaningful market moving effects, as we can see with investors such as Berkshire Hathaway.

Final thought

Allocating to large funds has its own challenges, because the allocator has to defend the lower alpha potential caused by fund behemoths (just ask any large manager and they can run you through those challenges). Ultimately, an institutional allocator is paid fees in order to fulfil their clients investment mandate. Which, in most cases, is superior risk-adjusted returns to the competition. The principal-agent problem can occur when an allocator factors in their own reputational risk when attempting to deliver outperformance.

Managing smaller pools of capital is often music to many fund allocator’s ears because they are able to be a bit more creative with their portfolios and allocate to names that differentiate themselves from other wealth managers.

There is a difference between liking a fund and being able to invest in it. Allocators depend on managers not only to perform (let alone have structures that are investable), but to get enough momentum behind the business so that they can write the tickets that many funds really need.